What is SMA?

Screening & Diagnosis

Living With SMA

Treatments

About Us

Contact Us

Back

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) is a condition that affects the nerves and muscles. Since it was first described in the 1890s, so much has been discovered about it. Living with SMA looks very different today than even a few years ago, following the recent development of treatments for the condition.

SMA is an inherited genetic condition. It affects motor neurons, which are special nerves in the spine that control muscle movement. When motor neurons do not work properly, movement can be limited or prevented, causing muscles to become weak and shrink (atrophy) over time. SMA can affect muscles used for moving the arms, legs and head, as well as breathing, coughing, eating and swallowing. SMA is part of a broader group of conditions called motor neuron disease, or MND.

There are treatments available that can help manage the condition and slow or stop the progression of SMA. The type of treatment depends on age of onset of SMA and the type of SMA diagnosed.

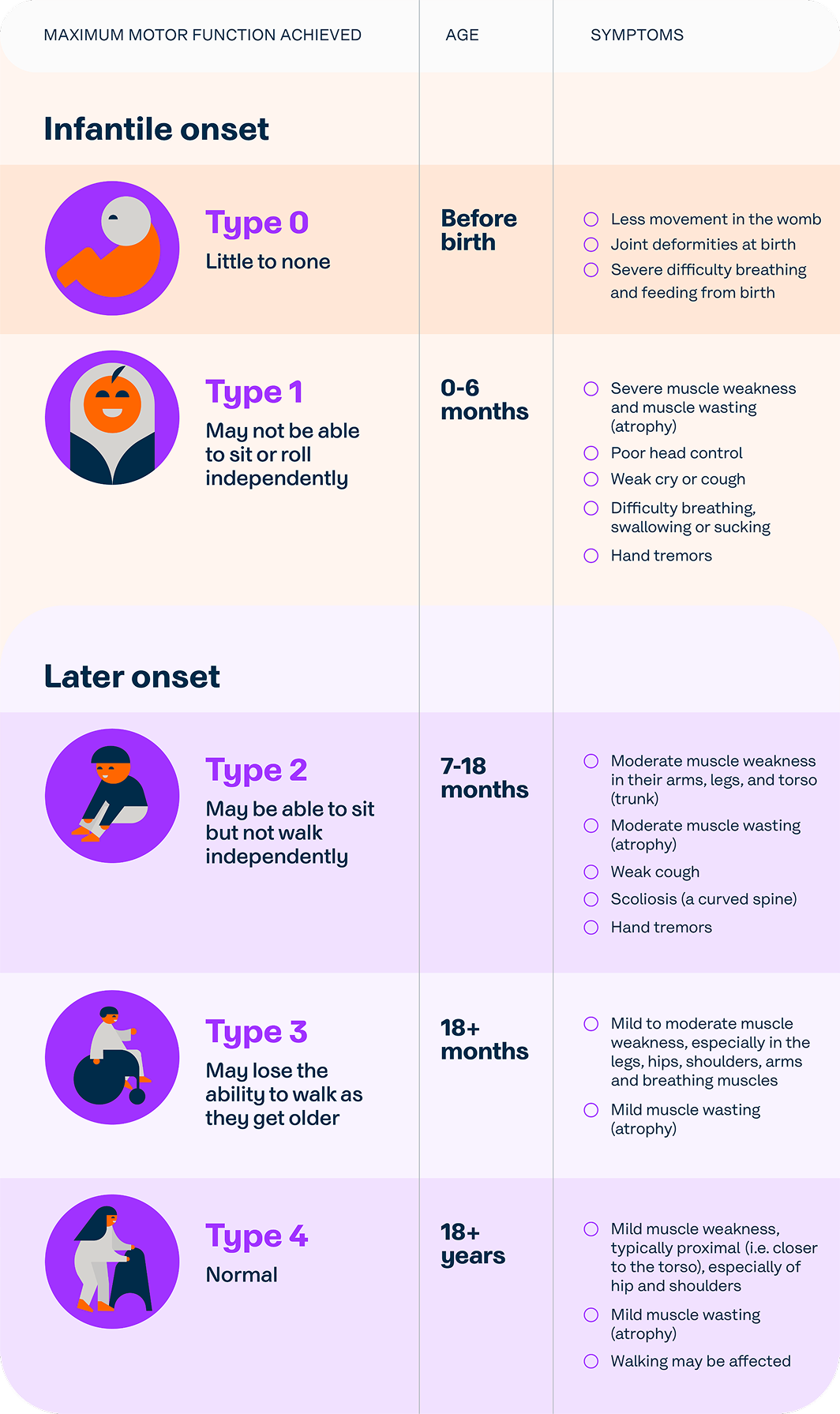

SMA is classified into different types, based on the age when symptoms start, how severe symptoms are and how symptoms affect life expectancy. The different types of SMA have varied effects on quality of life and different treatment options. Once diagnosed, speak to your neurologist to learn more about your specific type of SMA and the best management plan for you.

Symptoms are present in the womb

Symptoms appear between 0–6 months

Symptoms appear between 7–18 months

Symptoms appear during childhood, from 18 months

Symptoms appear in early adulthood

X-linked SMA, SMA with lower extremity dominance (SMA-LED) and SMA with respiratory distress (SMARD1) are types of SMA caused by changes to different genes

SMA symptoms can vary depending on a person’s age. The age when symptoms first appear helps doctors determine the type of SMA. If you are concerned about any of the symptoms listed below, speak to your doctor.

Muscle weakness and/or low muscle tone in the shoulders, arms, legs, torso, and/or hips — children may seem ‘floppy’

Poor head control

Difficulty breathing, swallowing or sucking

Weak cry or cough

Cannot sit or roll independently (0–6 months)

Able to sit but not walk independently (7–18 months) or loss of the ability to walk (18+ months)

Children with Type 2 SMA may have scoliosis (a curved spine) as muscle weakness can stop the spine from forming normally

Tremors or twitching

Less movement in the womb and/or joint deformities at birth (Type 0)

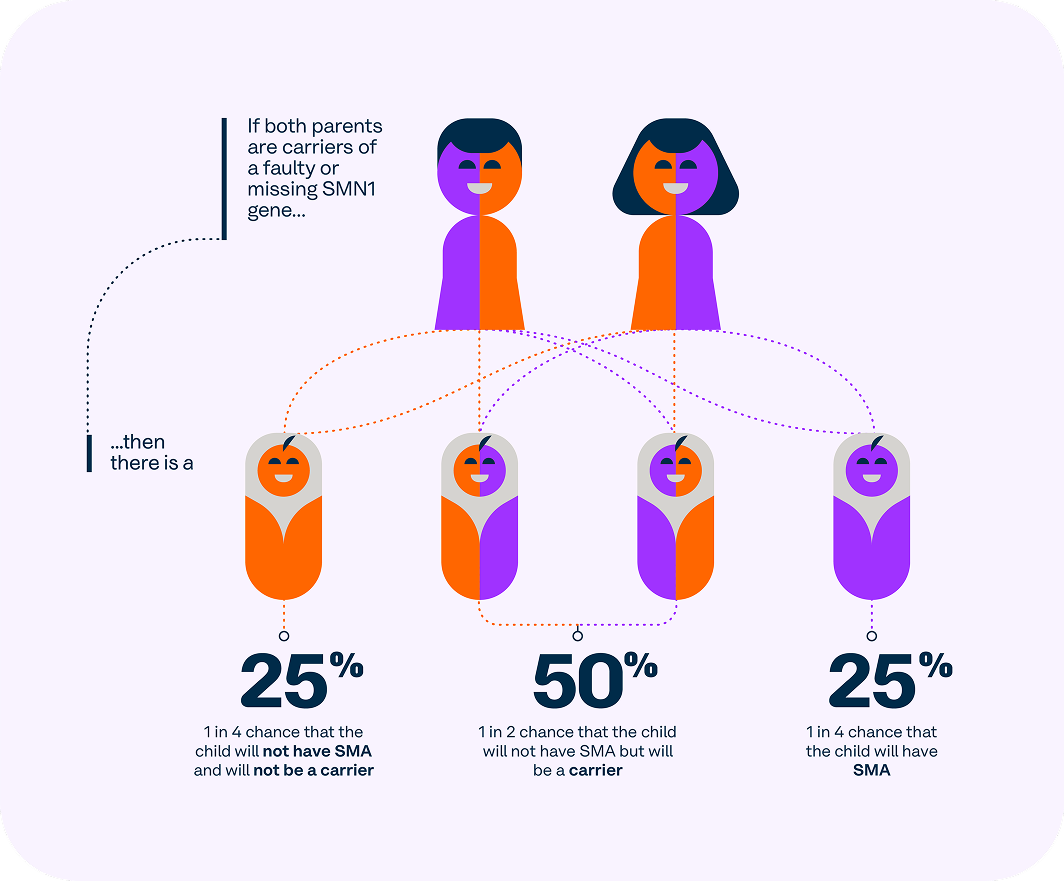

SMA is caused by a problem with a gene called Survival of Motor Neuron 1 (SMN1). Everyone has two copies of the SMN1 gene, one from each parent.

Sometimes, a person has one working copy of the SMN1 gene and one faulty copy. These people are called ‘carriers.’ Carriers do not have SMA because they have one working copy of the gene. If two carriers have children, there is a one in four (25%) chance their child will inherit two faulty copies of the SMN1 gene and develop SMA.

The SMN1 gene makes a protein called Survival of Motor Neuron (SMN). People with two faulty copies of the SMN1 gene may not make enough SMN protein, or any at all.

Without enough SMN protein, motor neurons (the nerve cells that control muscle movement) start to die. The loss of motor neurons is why SMA is referred to as a ‘neurodegenerative’ condition. This leads to the muscle weakness and shrinking (atrophy) that are characteristic of SMA.

Another gene, called Survival of Motor Neuron 2 (SMN2), also plays a role in SMA. It can produce small amounts of the SMN protein. Some people have more copies of the SMN2 gene than others. People with more copies of the SMN2 gene tend to have less severe forms of SMA. For children who have SMA but have not yet developed symptoms, the number of SMN2 gene copies they have can determine the type of treatment available to them.

For many years, there were no medicines available for SMA. However, innovation over the past decade has transformed the SMA landscape as families now have access to treatments.

Three medicines are currently available in Australia that can help slow or stop the progression of SMA. These treatments are not considered a cure for SMA but may improve muscle function and life expectancy. However, the long-term effects of these medicines are still being studied.

A multidisciplinary healthcare team will support you throughout your journey with SMA. This team should include a General Practitioner (GP), a neurologist, nurses and other healthcare professionals with experience in SMA. Other specialists such as a paediatrician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist and/or speech therapist can also make up the multidisciplinary healthcare team.

Additionally, people with SMA may require treatment for related conditions, including sleep disturbances, breathing difficulties and bone health issues.

Your healthcare team will provide detailed information about available treatments and develop a personalised management plan tailored to you or your child's needs.

SMA is caused by a problem with a gene called Survival of Motor Neuron 1 (SMN1). Everyone has two copies of the SMN1 gene, however, some people might have one working copy and one ‘faulty’ copy of the gene. These people are called ‘carriers’. Carriers do not have SMA, because of their one working copy of the gene.

If you have recently been made aware that SMA runs in your family, or have noticed symptoms that might indicate SMA in you or your child, speak to your doctor for more information about testing. Symptoms to keep an eye out for include:

If your child is diagnosed with SMA, they will have a certain type of the condition. Each type has a different impact on the quality and length of life, with different treatment options available for each type of disease. Further information can be found at our Children (0-12) Living With SMA page.

Since there is currently no cure for SMA, the goal of treatment is to manage symptoms and maximise quality of life. A team of healthcare professionals will help you throughout your journey, including a GP, neurologist and specialists, such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Three medicines are currently available in Australia that can help stop the disease from getting worse and may improve muscle function and life expectancy.

More information on treatments can be found at our Treatments page.

There are a range of support services available to people living with SMA, their carers and families.

Newborn screening is a way to identify common conditions that can be treated if caught early, minimising the impact on long-term health and survival. The NBS program is a free test offered to you a few days after your baby is born. If you agree to the testing, a midwife or nurse will prick your baby’s heel and collect a small sample of blood on a special filter paper card – a ‘bloodspot’ – which will be sent to a laboratory to test for conditions such as SMA.

This website is not intended to replace medical advice. Please speak to your healthcare professional for more information.

Join a powerful community of supporters who are helping tackle spinal muscular atrophy at its very core. Our community relies on us for support and best-practice resources to guide them in living well with SMA, as well as for resources to help raise disease awareness, educate others and advocate for people living with SMA in the wider Australian community.